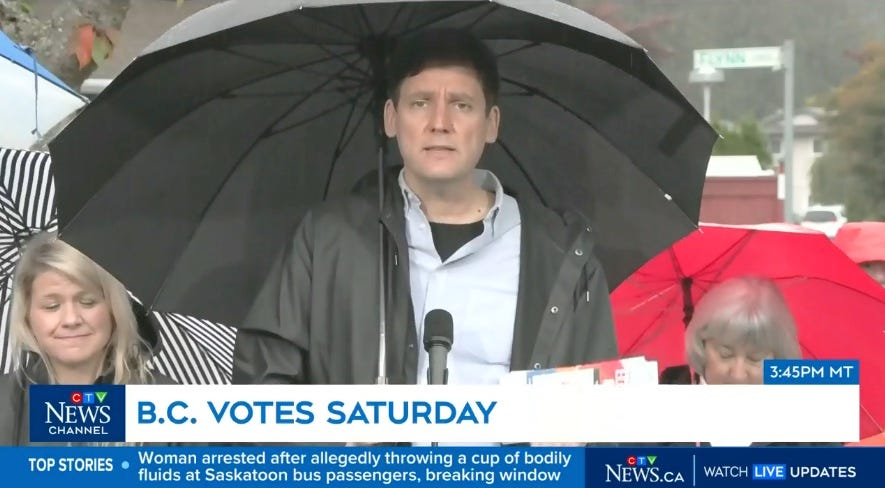

British Columbia's polarity shift: an election that changed the face of provincial politics

Although Premier David Eby's NDP eked out the narrowest of wins, the 2024 election saw the elimination of the existing 'free enterprise' option in favour of an insurgent BC Conservative party

This election report first appeared December 18 in Inroads, a Montreal-based journal of opinion.

Torrential rains lashed British Columbia’s Lower Mainland on election day, October 19. The atm…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to LOTUSLAND to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.