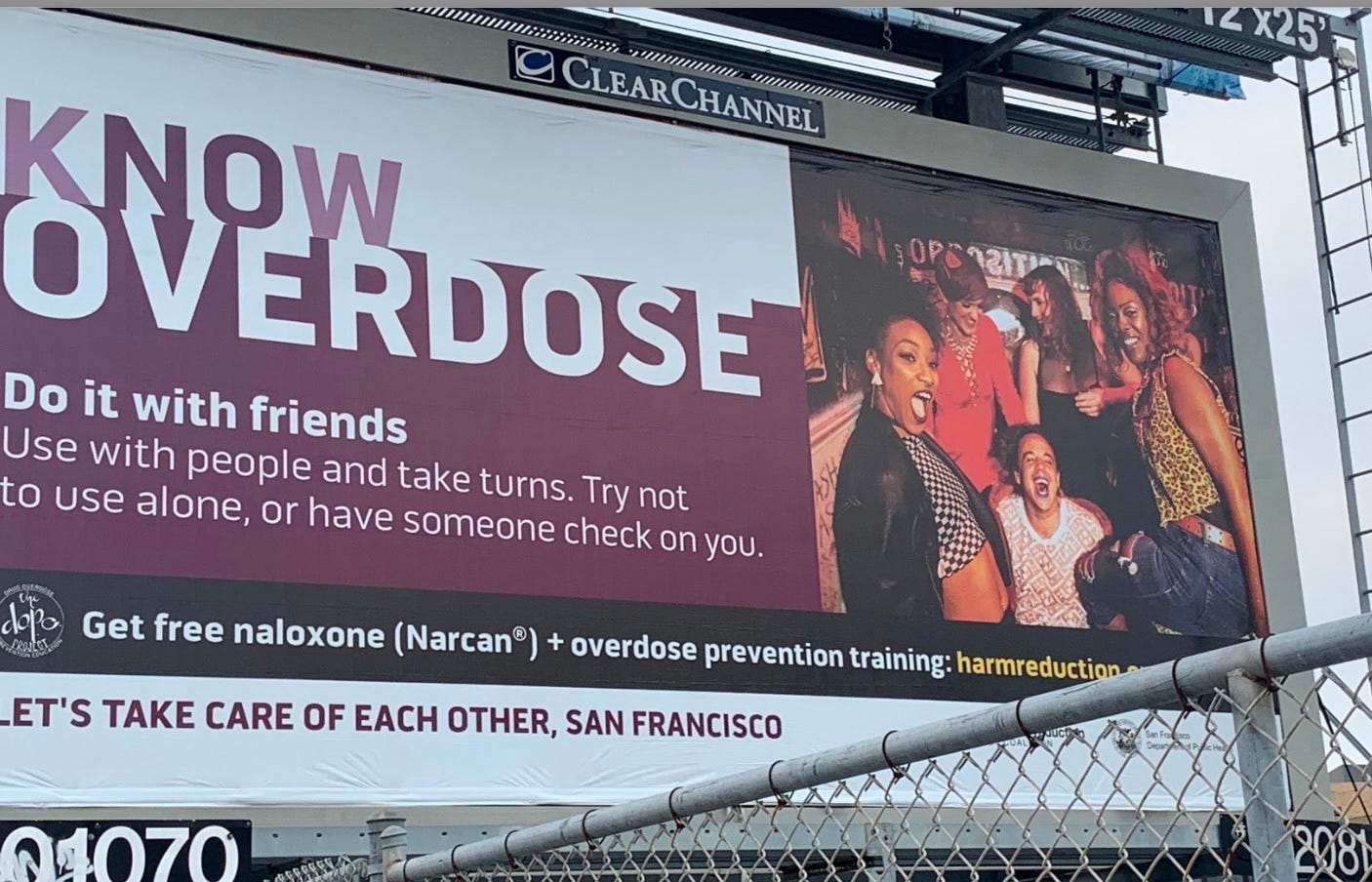

Have harm reduction advocates learned from their recent defeats?

Nearly ten years after BC's opioid emergency declaration, prospects for an effective response have never seemed bleaker. A US expert argues that feuding factions in drug policy wars have to make peace

With just ten months to go before the tenth anniversary of the declaration the declaration of BC’s toxic drug overdose em…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to LOTUSLAND to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.