How Rat Park, the BC "morphine on demand" experiment that upended addiction theory, shows a path out of the overdose crisis

As an Easter Weekend bonus. I'm reprinting one of Lotusland's most-read posts in 2024 about Bruce Alexander's path-breaking study on the roots of addiction in our globalized economy

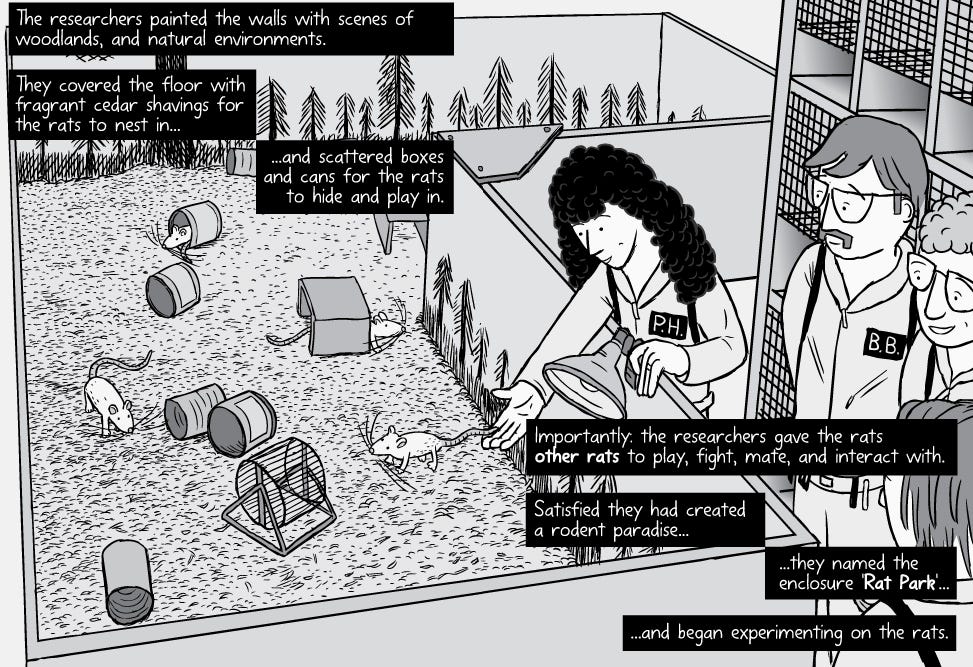

From a laboratory rat’s perspective, the enclosure constructed by four Simon Fraser University addiction researchers in 1978 was Utopia, 200 times the size of the usual rat cage, with forest-like decoration, exercise equipment, comfortable shavings, abundant food, many friends of both genders and, strangely, free morphine on demand.

In the months that followed, the residents of Rat Park, as it became known, largely ignored the morphine, upending countless experiments that seemed to show that a rat, mouse or monkey exposed to opiates would helplessly consume more, more and more.

This was proof, many thought, that drugs caused addiction, condemning anyone exposed to them to a living hell.

Rat Park contradicted that view. Happy rats, it seemed, were unlikely to be addicted rats.

The Rat Park experiment, compellingly recounted in a brilliant graphic novel by Australian artist Stuart McMillen, challenged long-held beliefs that the causes of addiction lie either in the drugs, with their malevolent and irresistible properties, or in the addicts, who are victims of some stigma or personal flaw.

Like Vietnam war veterans who recovered from heroin addiction after returning to the United States, Rat Park rodents that recovered from forced morphine consumption seemed to signal a new and hopeful way to confront addiction.

At a time when the toxic drug supply is BC’s leading cause of death, killing more British Columbians than murder, suicide, accidents and disease combined, this lesson seems more important than ever.

The ability of organized crime to produce, distribute and sell an infinite amount of contaminated opiates, stimulants and counterfeit pharmaceuticals is obvious. We know where the supply comes from.

But what about demand? Why is the market so large? Why so many addicts? (About 100,000 British Columbians are believed to have an opioid substance use disorder and an equal number to be occasional users.) If drugs are not addictive in and of themselves, what makes so many British Columbians vulnerable to substance use disorders?

The Rat Park story forces us to ask whether we are confronting an overdose crisis, a toxic drug supply crisis, or an addiction crisis, one with deep roots in society itself.

The Rat Park trials were not only a watershed in the analysis of addiction, they were a turning point in the career of lead researcher Bruce Alexander, a psychologist who had the audacity to ask if the rats’ morphine dependency was due to the experiment, not the morphine.

The addictions of lab rats tethered to an opioid-filled tube in their jugular vein, he suggested, were proving “nothing more than that severely distressed animals, like severely distressed people, will seek pharmacological relief if they find it.”

The unfortunate rats in the caged control group, able to deliver a dose with the push of a lever, consumed morphine at nearly 20 times the rate of the mellow Rat Park denizens. Yet even rats habituated to high doses of morphine in cages would quit using when released into the relaxing atmosphere of Rat Park.

Although Rat Park was soon dismantled, the questions it raised became Alexander’s life work, triggering decades of reflection that led him ultimately to what he later called the “dislocation” theory of addiction, the alienation which arises as the result of “the devastating psychological consequences of unrelenting societal fragmentation on individuals.”

Dislocation theory proposes that all human beings require psychosocial integration, a sense of identity as well as engagement with society and nature. Anyone without this basic connection to community experiences dislocation and is at risk of addiction. In this respect, addiction or substance dependency is a rational response to an unfulfilled need.

Along the way, Alexander refined the definition of addiction to mean “neither a disease nor a moral failure, but a narrowly focussed lifestyle that functions as a meagre substitute for people who desperately lack psychosocial integration.”

Addiction can be “overwhelming involvement with any pursuit whatsoever that is harmful to the addicted person and his or her society” from online gaming to abuse of power.

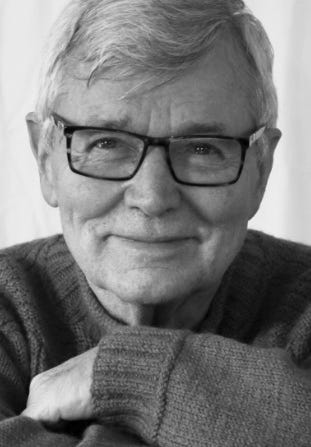

“It doesn't matter if we call it addiction or we call it something else,” Alexander told me in a recent interview on Pender Island, where he now spends much of his time. “It's still the fact that people fill this void with fanatical devotion to things which are not always good for them.”

“When I talk to addicted people, whether they are addicted to alcohol, drugs, gambling, Internet use, sex, or anything else,” Alexander wrote, “ I encounter human beings who really do not have a viable social or cultural life. They use their addictions as a way of coping with their dislocation: as an escape, a pain killer, or a kind of substitute for a full life.

“Maybe our fragmented, mobile, ever-changing modern society has produced social and cultural isolation in very large numbers of people, even though their cages are invisible!”

Vancouver, he realized, was a perfect human-scale Rat Park, apparently the “best place on earth,” an urban jewel set amid mountains and ocean, yet experiencing the highest levels of substance use abuse in Canada. If we’re having so much fun, sailing during the day and skiing in the evening, why are so many of us miserable?

In The Globalization of Addiction, his summary of a lifetime of research, Alexander wrote, “Vancouver has been Canada’s most drug- and alcohol-addicted city and British Columbia its most drug and alcohol-addicted province by a plethora of quantitative measures: per capita consumption of alcohol, death rate attributed to alcohol, prevalence of alcoholism, death rate due to heroin and cocaine overdose, prevalence of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection and hepatitis C infection among intravenous drug users, availability of heroin and cocaine, self-reported use of all illicit drugs, arrest rates for drug crimes, cost of illicit drug use, and drug-related homicides.”

B.C. accounted for 61 percent of all heroin arrests in Canada, was the centre of a marijuana industry with annual turnover in the billions of dollars and in 2004, had a higher per capita consumption of cannabis, cocaine, crack and ecstasy than any other province in Canada.[1]

Little has changed since Alexander made that claim in 2008. According to Health Canada, “In both 2019 and 2020, loads of fentanyl per capita [in wastewater samples] were more than four times higher in Vancouver than in any other city” in Canada.

Why Vancouver?

Having first displaced First Nations, Alexander concluded, B.C.’s newcomers poured in from every continent on earth, themselves dislocated by poverty, war, revolution and the upheavals of a free market global economy. A B.C. economy defined by speculation and resource extraction amplified the turmoil. For some, it is too much.

While a free market economy generates enormous wealth and innovation, Alexander conceded, it also “breaks down every traditional form of social cohesion and belief, creating a kind of dislocation for the poverty of the spirit that draws people into addiction.” Vancouver is “a display case for an intractable addiction problem that is still spreading throughout the world.”

In 2022, 40 years after Rat Park, Alexander gave a final academic lecture to the Addiction Theory Network, listing the long series of addiction strategies, including harm reduction, that have failed to turn the tide.

Despondent at the lack of progress since the Rat Park experiments, he warned his colleagues that their work was stagnating, that progress against the harms of addiction had stalled. Why?

“Mass dislocation has real benefits for economic growth and geopolitical power,” he acknowledged. “The free market system that underlies the modern global economy needs dislocation.” Many can’t live with the resulting dislocation, but our economy can’t live without it.

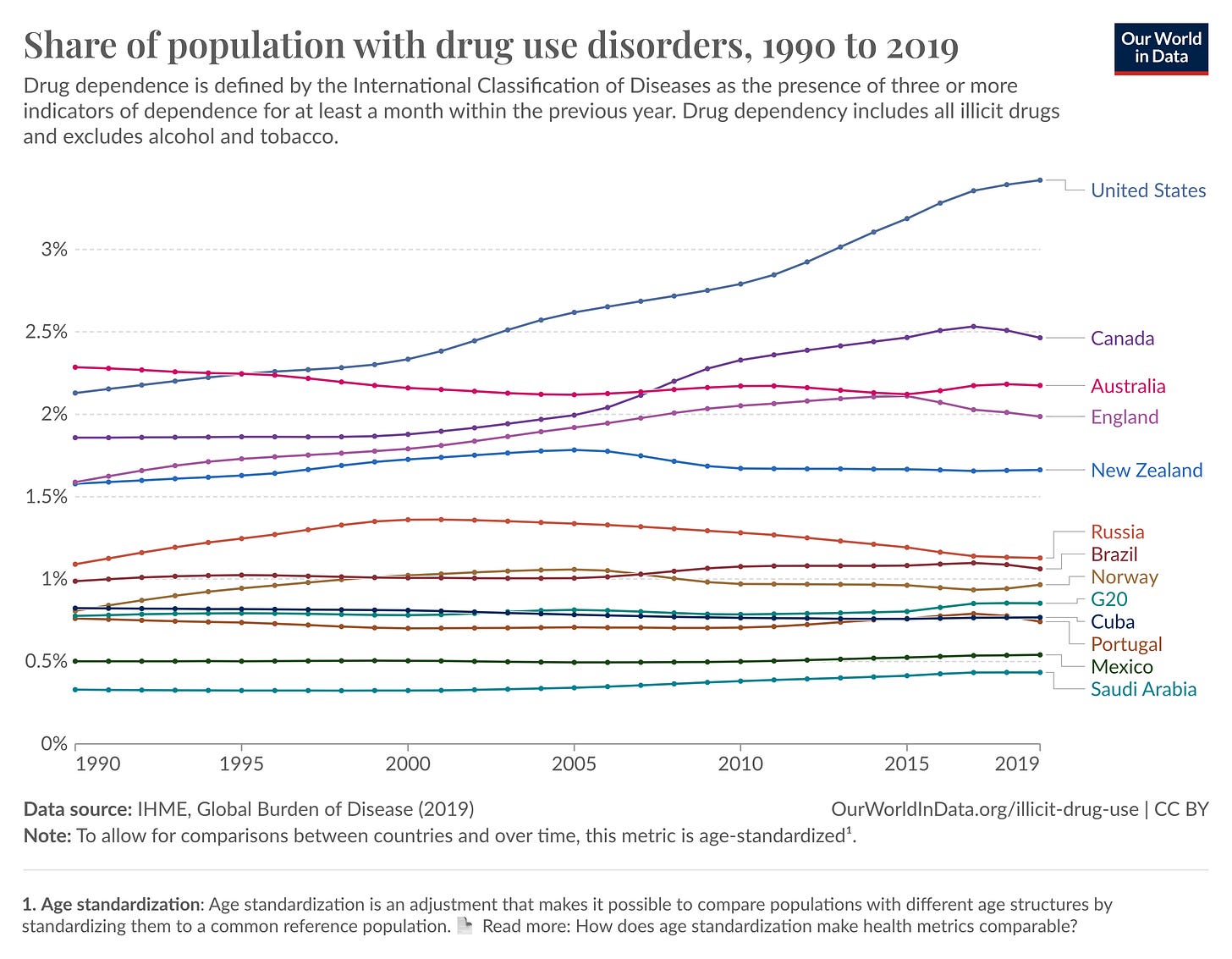

The result, in a free market economy like Canada’s, is a rising tide of addiction. Indeed, Canada is second only to the United States when scientists calculate the share of the population with drug use disorders. (Alexander is quick to note that so-called socialist societies like the Soviet Union or revolutionary China have produced their own massive dislocations.)

Tragically, a globally competitive illicit narcotics industry has grown to meet and expand demand, even shipping surplus production to offshore markets.

As Alexander wound up his academic career, he challenged his colleagues to go beyond the role of healer or theoretician to become “agents of social change.”

“Can we confess that we cannot therapize or theorize our way out of [the addiction crisis],” Alexander asked, “nor overcome it with harm reduction or new drug legislation or social housing?

“I do not know how a world society of eight billion people facing jet-propelled technological modernization, political chaos, and ecological disaster can function well enough that most people can put together the reasonably full lives that can protect them from dangerous addictions. I do know that this question must be faced, because the dangers of mass addiction are so enormous.”

The hopeful message of Rat Park is that addicted rats could recover if transferred from their cages to the wide open spaces of the park. Alexander is not proposing that we wait for a global revolution to tackle addiction, just that we be honest about the problem and start taking the steps necessary to confront it.

[1] Bruce Alexander. The Globalization of Addiction: A Study in the Poverty of the Spirit. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008. 20. Alexander’s work was a springboard, in part, to Dr. Gabor Mate’s In the Realm of the Hungry Ghost: Close Encounters with Addiction, Toronto: Vintage Canada, 2008. Also based on experience in the Downtown Eastside, Mate’s work became an international best seller. Alexander sees Mate’s work as completely aligned with his own, but jokes that Mate focuses on “Big T trauma, like childhood abuse,” whereas Alexander’s own work studies “little T trauma” present in the dislocations of most peoples’ lives.

Thanks, Geoff, great article!