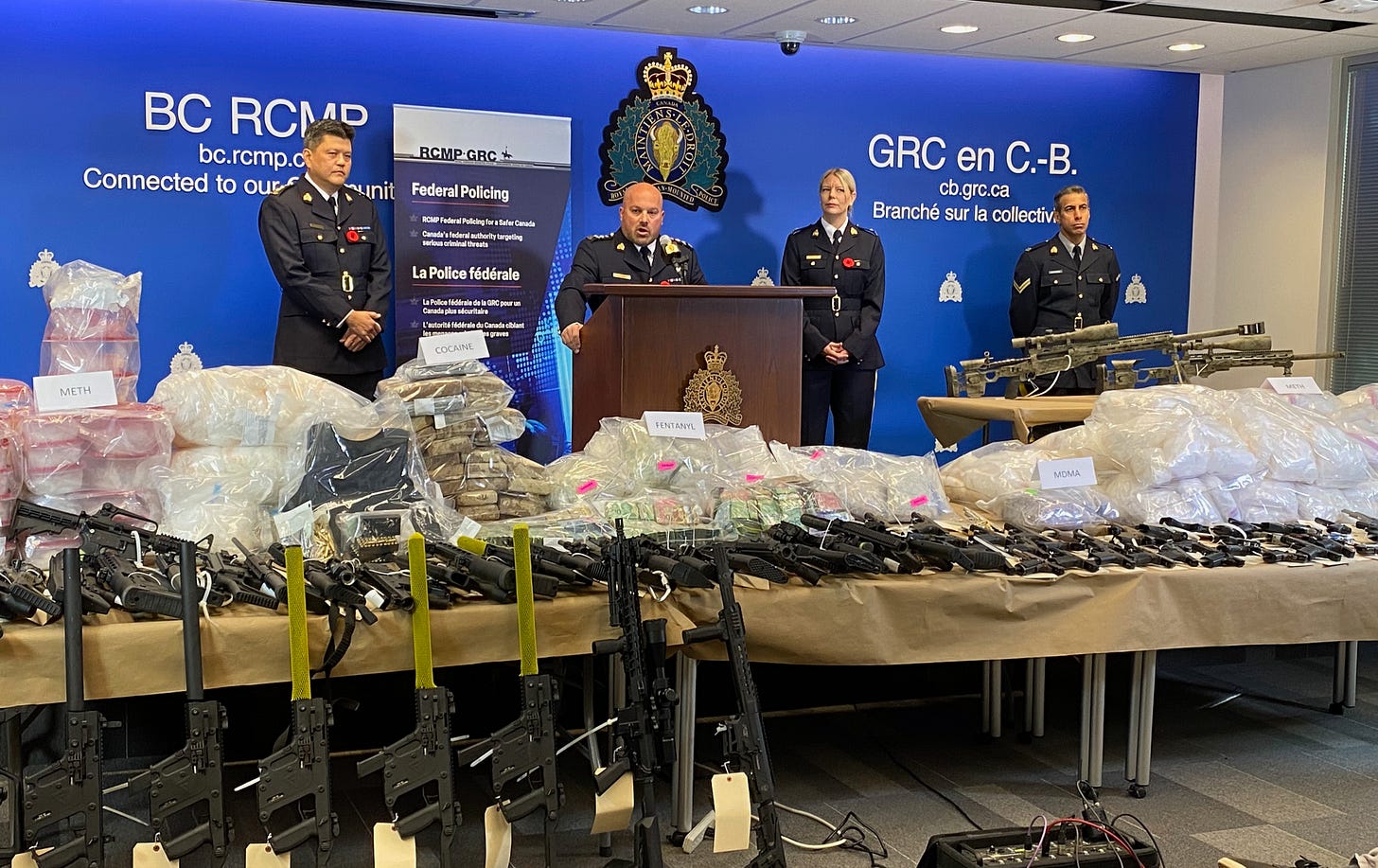

RCMP shuts down largest superlab in Canadian history, a 'supermarket of criminality'

A 50-calibre machine gun, a "war weapon," was among 87 firearms seized October 25, proof that superlab operators were ready for anything to protect $485 million in profits

The 50-cali…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to LOTUSLAND to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.