How Trump's new 'war on drugs' could make everything much worse

Repression of the drug trade always fails, in part because so many profit from it in the legal economy, but increased violence in Mexico has already had dire consequences elsewhere in North America

Canada is about to become a foot soldier in Donald Trump’s transcontinental war on drugs, despite the complete failure of that strategy wherever it has been attempted.

There is every possibility that joint action by Mexico, the US and Canada against “narco-terrorism” will worsen the overdose crisis, triggering more violence and dislocation, and building on the waves of overdose deaths triggered by previous “wars.”

In fact, battles in the “war on drugs” fought in Mexico can quickly have consequences in Canada.

Why does the war on drugs never end? In part because it fails to tackle the causes of addiction, which is rooted in dislocation, poverty and inequality.

But according to a recent and unique survey of the North American drug trade, “the so-called war on drugs endures because, while it is detrimental to human security, it provides benefits for a variety of stakeholders that link the United States, Mexico and Central America in licit and illicit fashions.”

In other words, many people make money from the drug business, not just the dealers, and they want to keep doing it.

Writing in 2022, long before Trump 2.0, Cecilia Farfán-Méndez, a leading American expert on organized crime and North American head of the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime, worked with other scholars to show how repression of the Mexican drug trade worsened violence, cost thousands of lives and produced a corrupted military regulating the business in its own interest.

(The studies comprised an entire issue of the Journal of Illicit Economies and Development, published in 2022.)

The drug trade was fine as long as it did not interfere with government. (These days, of course, some cartel leaders would like to be the government as well.)

Now, determined to avoid Trump tariffs and US military attacks on cartels within the country, Mexico has again stepped-up repression. Canada is expected to follow suit.

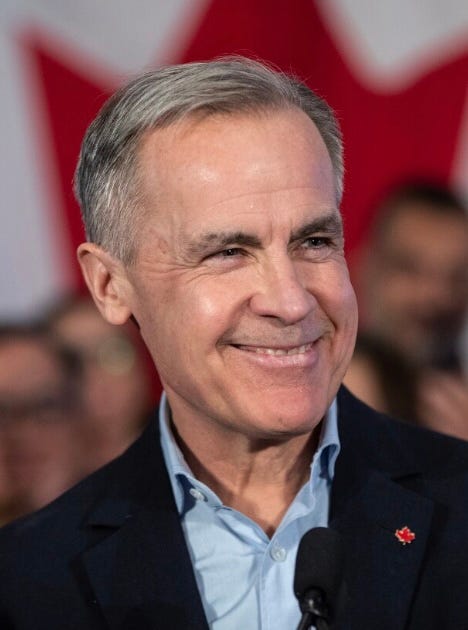

Long before Prime Minister Mark Carney expressed interest in sheltering Canada under Donald Trump’s Golden Dome anti-missile defence system, the Trudeau Liberal team had already splashed out $1 billion to respond to Trump’s anxieties about fentanyl exports and illegal immigrants along the 49th parallel.

There were no fentanyl exports and few refugees, but Ottawa quickly leased two Black Hawk helicopters, a gold standard symbol of military power, to show respect. Canada also agreed to list several cartels as “narco-terrorist” organizations.

Mexico’s military had engaged with cartel gunmen long before Trump was elected. Now, President Claudia Sheinbaum has extradited scores of top cartel leaders to the US for trial and repression of organized crime, eased under her predecessor, is increasing again.

Since Mexico’s crackdown on cartels began in 2006, the country has experienced widespread and intensive violence, claiming 300,000 lives, leaving another 100,000 missing, and displacing hundreds of thousands more who then fled their homes for the United States.

Now, instead of seeing the migrant crisis as the result of the drug war, “migration and the illicit drug trade are conflated as a security threat to the United States,” says Farfán-Méndez. The US administration is expecting a new round of violence to succeed where previous efforts failed.

When you talk about crime and politics in Latin America, says Farfán-Méndez, you are usually talking about the one and the same thing. They are, “in reality, entirely porous worlds, in which the use of criminal resources to exert state power is often a constituent part of the ‘democratic order.’ High-level crime, far from revealing a failure of state institutions, reflects a degree of state power.”

The collaboration between the criminal underworld and the legal economy occurs along the entire supply chain from the poppy fields to the point of sale. In Latin America, public institutions seek to “regulate illegal markets, rather than dismantle them.”

Why destroy the drug trade when cocaine transhipment, for example, “has become an engine of dramatic socioeconomic and environmental change in Central America?” The cocaine business, with revenues topping $100 billion a year, has helped shape the entire economy of the region.

Both Guatemala and Honduras earn more annually from cocaine sales than they do from foreign direct investment. Even Donald Trump will have a hard time making them give it up. (In 2022, ex-Honduran president Juan Orlando Hernandez was sentenced to 45 years in prison in a New York courtroom for his role in exporting 400 tons of cocaine to the US over a ten-year period.)

Repression in Latin America can have direct and fatal consequences far to the north. Fernando Montero and two colleagues writing in the same journal traced the changes in the regional street drug markets of Philadelphia and Tijuana to understand why heroin was replaced by fentanyl, xylazine and methamphetamines. They found the explanation in linkages stretching all the way back to Colombia and Mexico.

As is the case everywhere, “war on drugs” policing policies in Philadelphia made life miserable for street level dealers while ignoring both wholesale narcotics dealers, who were responsible for adulteration of the drug supply. Police also ignored “financial institutions laundering narcotics profits” collected at the wholesale level.

Even more disturbing was the fact that “war on drug” policies in Central America, including crop eradication programs, drove up the cost of conventional opioid crops and accelerated adoption of fentanyl, first to extend heroin supplies and then as a complete substitute.

Fentanyl requires negligible labour, a small lab, is easy to smuggle and indifferent to drought, pests and other blights of regular heroin production. With the addition of xylazine, the fentanyl high can be extended for even greater efficiency. In a few years, cartel-produced synthetic opioids had forced heroin off the market.

The result has been an economic catastrophe in the poppy-growing regions of Mexico and a wave of overdose deaths in retail markets, including here in Canada.

Where Canada will fit in this new war on “narco-terrorism” remains unclear, but if history is any guide, violence and repression in Mexico can have deadly repercussions right here at home.